How can a focus on material culture help us better understand the ways that displaced people navigate the challenges of urban life? In this piece, William Montieth explores the (in)visibilities of refugees through the joint lenses of urban economies, and material culture. Through the wax fabric (kitenge) industry in Kampala (Uganda), Congolese refugees are rendered not only as economic agents but also as key contributors to vibrant, and historically-situated, material cultures in a context that is otherwise precarious, lacking in legal protections or formal humanitarian support. This focus on kitenge forces us to re-think displacement in urban contexts, the diverse roles that refugees play in otherwise precarious and insecure urban settings, and different ways of researching displacement itself. These are, in turn, questions that we are exploring in relation to urban displacement in Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. This article forms part of the exhibition ‘African Mobilities: This is Not a Refugee Camp,’ convened at the Architekturmuseum in Munich between 25 May to 18 August 2018. See AfricanMobilities.org for further information. For more on these themes, see the suggested readings at the end of this piece.

The Patterned Legacies of Displacement in Uganda: Reflections from the African Mobilities Exhibition

Dr William Monteith (Queen Mary University of London) with Doreen Agendo, Randi Karangizi, Nina Peters and Joel Ongwech

Visibility is a double-edged sword for displaced populations in urban settings. On the one hand, towns and cities provide a welcome measure of invisibility to refugees fleeing harassment and persecution. On the other hand, urban economies often compel displaced groups to participate in highly visible business ventures in order to make a living in the absence of state or formal humanitarian support. While complete visibility runs the risk of detection and discrimination, complete invisibility may facilitate socio-economic isolation and destitution. Urban displaced populations thus walk a tightrope between disclosure and concealment as they establish their lives in the city.

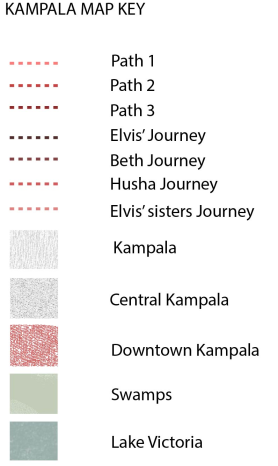

In Kampala (Uganda), Congolese refugees have rendered themselves visible through their participation in the wax fabric (kitenge) trade, contributing to a vibrant material legacy of displacement in the city. Inspired by the challenge laid down by the African Mobilities Exhibition, we set ourselves the task of (re)thinking migration and displacement in the city from the perspective of a particular material product, rather than a population or policy. Combining representations from architecture, film and cartography, we examined the ways in which kitenge has transformed the social, economic and built environment in Kampala, while acting as a historical repository for powerful ideas about identity and belonging.

The contemporary geographies of the wax fabric trade can be traced back to European colonialism. In the mid-nineteenth century, a Dutch merchant family appropriated and industrialised an Indonesian batik method of waxing and printing fabric and established a market for this fabric in West Africa. However, once on the continent, wax fabric took on a life of its own. Batik prints were re-appropriated and adapted in line with local styles and techniques including tie-dying and resist-painting, and marketed by West African cloth traders. Print-production factories proliferated in the region, generating a sense of local connection and ownership. Manufactured wax fabrics became everyday dress in Nigeria, Mali and Senegal, and a prestigious mainstay of twentieth-century fashion in Ghana.

Kitenge played an important role in the project of ‘indigenisation’ in post-colonial Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which included the deliberate removal of European products and fashions. Wax fabrics came to symbolise Congolese independence, with new editions commissioned on each anniversary. Today, different prints are used to communicate a variety of different messages; from a person’s politics to their marital status. For example, in 2015, a kitenge print containing the phrase ‘La maman est aussi important que le papa’ (‘The mother is as important as the father’) became popular among women protesting the restricted political rights of women in DRC.

However, despite its prominence in West and Central Africa, kitenge did not enter into popular circulation in Uganda until the early 2000s, when it was brought by Congolese populations crossing the border in the wake of the Kivu conflict. Initially seen as something ‘for the Congolese’, kitenge has become increasingly popular in Uganda in recent years as a result of both its emergence in the global music and film industries, and the successful marketing strategies of traders in Kampala. Congolese traders purchase kitenge prints from manufacturers in Ghana, Holland and (increasingly) China, and distribute them through mobile networks of hawkers in the city. They market their products by ‘moving with them’ to prominent events, including weddings and church services, and in doing so, weave themselves into the cultural fabric of the city.

Kitenge is also transforming the architectures of downtown Kampala. Zaina Plaza has become the centre of the wax fabric trade, in which Congolese and Ugandan vendors operate from 3×3 metre shops (the legal minimum for a commercial space in Kampala), decorated with patterns that connect Kampala to cities in Europe, East Asia and West Africa.

Kitenge is also transforming the architectures of downtown Kampala. Zaina Plaza has become the centre of the wax fabric trade, in which Congolese and Ugandan vendors operate from 3×3 metre shops (the legal minimum for a commercial space in Kampala), decorated with patterns that connect Kampala to cities in Europe, East Asia and West Africa.

By transporting and trading kitenge in Kampala, Congolese residents render themselves visible as people of Kampala, and key contributors to urban fashion and the economy. However, they also mobilise larger ideas, such as those of pan-African identity and voisinage – ideas emblazoned on the prints – that challenge the delineation between ‘citizen’ and ‘refugee’ promulgated by governments and development agencies.

*

Featured Image: Elvis Lembe, a Congolese fabric trader, transports kitenge to his shop in downtown Kampala (Joel Ongwech, 2017)

*

Read more pieces from the Refugee Hosts blog here:

Ager, A. (2017) “Sounds from Hamra, Lebanon”

Angelie Saggar, S. (2017) “Space of Refuge Symposium Report”

Blachnika, D. (2017) “Refugees. Present/Absent. Escaping the Traps of Refugee (Mis)Representations”

Carpi, E. (2018) “Assessing Urban-Humanitarian Encounters in Northern Lebanon”

Davies, D. (2017) “Urban Warfare, Resilience and Resistance: Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi (2015)”

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (2016) “Refugees Hosting Refugees”

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (2017) “Space of Refuge: Opening Night”

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (2017) “Representations of Displacement – Series Introduction”

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. and Qasmiyeh, Y. M. (2017) “Refugee Neighbours and Hostipitality”

Greatrick, A. (2018) “Sounds from Istiklal, Turkey”

Grewal, Z. (2018) “A Successful Alternative to Refugee Camps: A Greek Squat Shames the EU and NGOs”

Sharif, H. (2018) “Refugee-led Humanitarianism in Lebanon’s Shatila Camp”

Thieme, T. (2018) “World Refugee Day – DIY Humanitarianism in Paris”

Western, T. (2017) “ΤΣΣΣΣ ΤΣΣΣ ΤΣΣ ΣΣΣ – Summer in Athens: A Sound Essay”

1 comment