Who is it that we choose to see and who is‘unseen’? How can we think and respond differently to the world around us? In this piece Dom Davies adds to his series of blogs on Refugee Hosts exploring our emotional, political, cultural and social responses to the architecture and geography of border regimes, and to those contained within, and excluded by, these constructed architectures and geographies. By using the text of China Miéville’s The City & the City, Davies argues that we can understand geography, not as a constituted territory, but as a ‘socially constructed, legally demarcated and politically contingent manipulation of actually existing space.’ Davies goes on to examine what is learned and then policed within these social and political constructs, enabling us to question what or who it is we have learned and continue to learn to see and ‘unsee’. In relation to the work of Refugee Hosts, this piece offers an additional perspective on displacement from and within familiar and distant geographies and can be read as part of our Representations of Displacement Series.

If you find this piece of interest please also see the suggested readings at the end of this post.

Speculative Borders: China Miéville’s The City & the City

by Dominic Davies, City University of London

The speculative novels of author and activist China Miéville conjure fantastical worlds that, though filled with alien creatures and steampunk technologies, afford us space to think differently about the violent social and political realities of our own. Consider Miéville’s Bas-Lag trilogy (2000-2004), set in the large, fictional city-state of New Crobuzon. After a surge in unnatural meteorological turbulence, this pre-modern civilisation assembles a huge, underground machine known as the ‘aeromorphic’ engine in a failed attempt to regulate the ensuing climate precarity. Or consider the distant planetary landscape of his novel Railsea (2012), which has become so soft and malleable that it has been infiltrated by giant mole-rats who, carving their way through the earth, make stable civilisation impossible. In order to survive, whole cities must move along a web-like infrastructure of iron rails – the titular ‘railsea’ – that criss-cross over the soft earth and allow passage between its harder segments. As Terence Cave (2018) observes, Miéville’s peculiar linguistic collocations – ‘aeromorphic’, ‘railsea’ – create worlds that are both familiar and strange, distant yet recognisable. Miéville extrapolates the normalised extremities of our own world into such absurdist speculative scenarios that we are allowed to see them afresh, and to reflect critically on the conditions that give rise to them.

Miéville’s most popular and widely celebrated novel, The City & the City (2009), repeats this formula. However, unlike the Bas-Lag trilogy and Railsea, the world of this novel is recognisably our own, the action playing out in two cities located somewhere on the Eastern edge of modern Europe. While these two cities, Besźel and Ul Qoma, are themselves fictional, the wider continental geography is not. The novel is both of and against our ‘real’ world.

But Miéville’s two cities are undeniably weird. For while Besźel and Ul Qoma are two markedly different places, they occupy much of the same geographic space. Each city has its own citizens, its own cultures, even its own culinary delicacies; and they each have separate governments, political borders, police departments and immigration procedures to match. The problem, for Besźel and Ul Qoma, is that they are ‘cross-hatched’ – Miéville’s word. Their territories are not separated by a single border, but are rather enmeshed into a dizzying patchwork of intermingling territories. For example, different segments of a single street might fall into one or other of the cities: a cluster of buildings might be in Besźel, but it is possible for sections of the surrounding pavement and road to be in Ul Qoma.

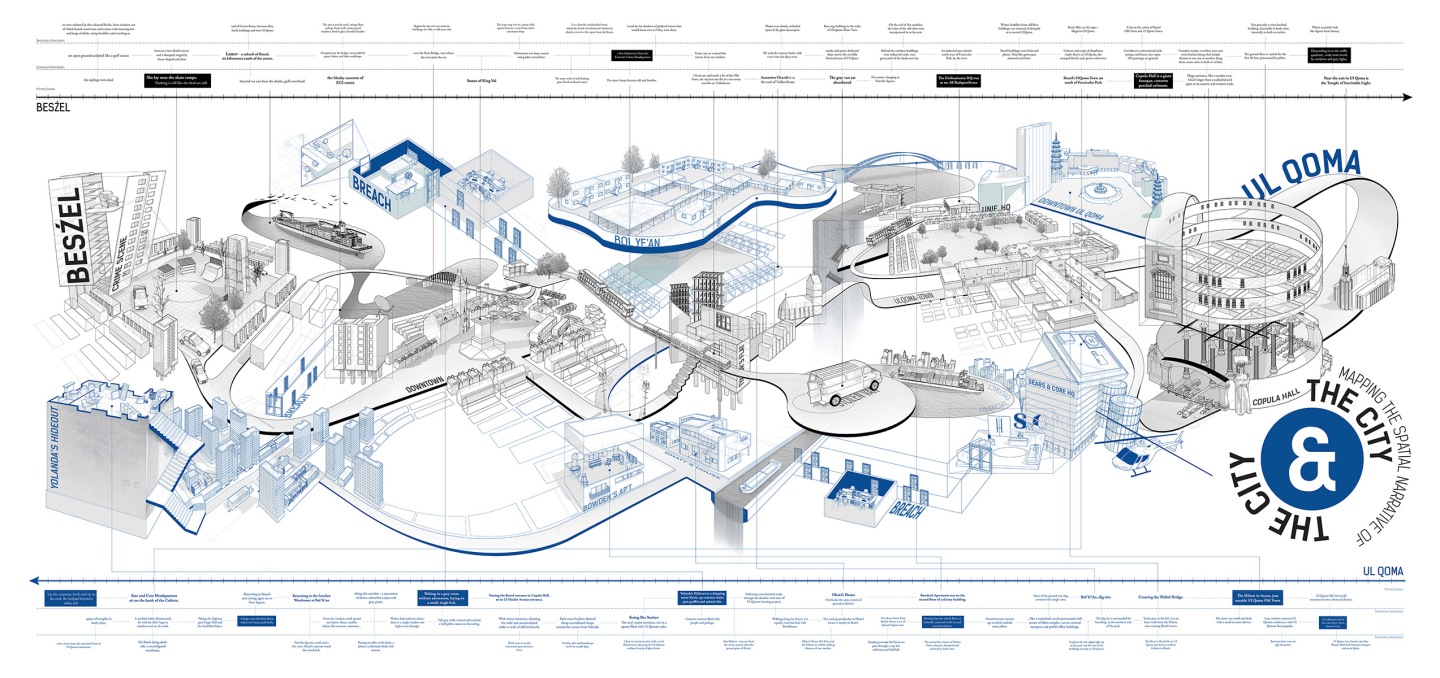

Despite, or perhaps because of, this close proximity, the borders between the cities are tightly regulated, and Miéville devises a number of other collocations to describe the spatial physics of Besźel and Ul Qoma. Border fortifications alone are not enough to demarcate between citizens that, though inhabiting the same space, are restricted to two separate places. People in one city must therefore ‘unsee’, ‘unhear’ and ‘unsense’ those in the other. A sinister, Stasi-like, extra-legal militia force called ‘Breach’ comes down hard on anyone who fails to observe these borders. Locals are educated into the process of ‘unseeing’ from childhood, while visiting tourists must undergo a training procedure before stepping foot in either Besźel or Ul Qoma – they cannot visit both at once. A citizen of Besźel can visit Ul Qoma, but to do so they must acquire the correct paperwork and pass through the single authorised border crossing located in Copula Hall, a large administrative building at the centre of both cities. The dark irony of such an elongated procedure is not lost on Miéville; on one occasion in the novel, the protagonist, Tyador Borlú, makes the long journey to Copula Hall to leave his home city legally, only to visit a building in Ul Qoma that is right next door to his own apartment in Besźel. (A trailer for the BBC’s valiant attempt to dramatise this bizarre universe can be seen here).

The allegorical power of Miéville’s thought experiment is somewhat obvious. As we enter the narrative, we are forced to think of place not as a geographically constituted territory, but as a socially constructed, legally demarcated and politically contingent manipulation of actually existing space. The politics of the division between Besźel and Ul Qoma is heightened as it becomes apparent that the former is a poor, dilapidated city in need of infrastructure investment, while the latter is a prosperous citadel of urban modernity, its skyline emblazoned with skyscrapers and cut through with high speed trains.

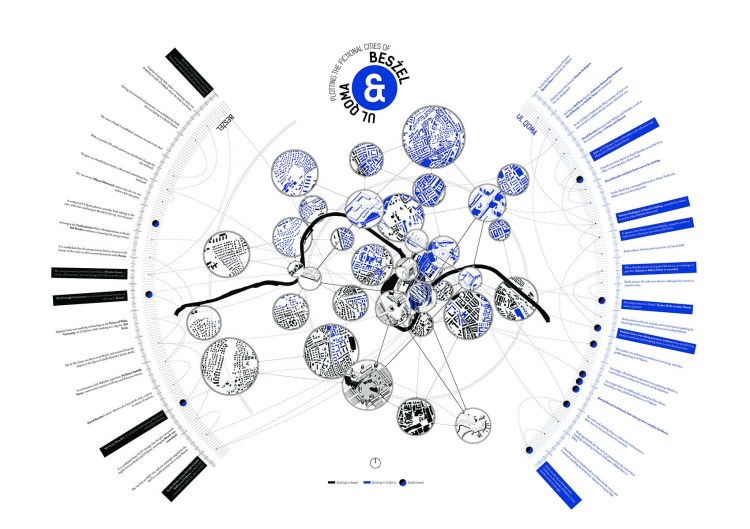

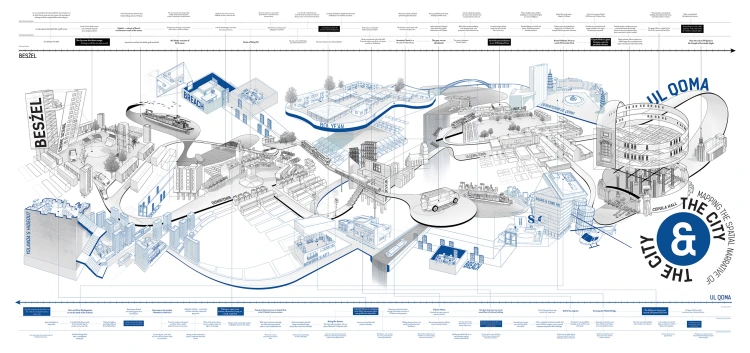

As the narrative progresses, what at first appears as a bizarre and unbelievable conceit becomes in fact an all-too-familiar condition that is common to all cities, both historic and contemporary. For example, architect Simone Rowe’s visual maps of Miéville’s two fictional cities bears uncanny resemblance to Charles Booth’s 1889 map of London’s poverty. Where for Booth the blue segments indicate poverty and the red indicate wealth, we might easily use his map to visualise the ‘cross-hatched’ layout of Besźel and Ul Qoma. We all know what it is to move through a city, unseeing those spaces to which we do not have a right, or that we would prefer to ignore. All that Miéville has done is to take these socio-spatial dynamics to their logical extreme.

A number of commentators have thought with and through Miéville’s speculative novel to understand how, as Deborah Cowen (2017) remarks, our regular ‘unseeing is not a natural or automatic fact but a practice that is learned and aggressively policed’. But beyond revealing the socially constructed and imagined quality of political borders, as well as the absurd logic of their hysterical regulation, The City & the City has something more specific to teach us about the ways in which space is felt and imagined by refugees in particular. Indeed, Miéville’s novel contains an oft-overlooked subtextual commentary on a ‘refugee crisis’, several years before the term entered common vocabulary in Europe in 2015.

Miéville’s protagonist, Tyador Borlú, is a police inspector who throughout the narrative attempts to solve a murder. The catch is that the murder took place in Besźel, but that the murderer seemingly committed the crime from Ul Qoma. There is no spoiler alert here: you must read the book for yourself to untangle this murder mystery. But it is by combining his speculative narrative with the searching poise of crime fiction that Miéville asks us to lean in and ‘detect’ for ourselves. Just as we find ourselves asking, with Borlu, who is the murderer, so we are also encouraged to ask, what is the book really about?

Assuming the posture of the detective, we can assemble a series of clues from Miéville’s narrative to discover a frighteningly accurate anticipation of Europe in 2019, a full decade after the novel’s original publication. Consider the following exchange between Borlu and his deputy, Corwi, as they discuss in an early scene Ul Qoma’s new, hard right nationalist politician, Major Syedr:

‘Since Syedr’s lot came into the coalition screaming about national weakness the government’s fretting about seeming too eager to invoke, so they’re not going to rush. They’ve got public enquiries about the refugee camps, and there’s no way they’re not going to milk those.’

‘Christ, you’re kidding. They’re still freaking out about those few poor sods?’ Some [refugees] must make it through and into one city or the other, but if they did it would be almost impossible for them not to breach, without immigration training. Our borders were tight. Where the desperate newcomers hit cross-hatched patches of shore the unwritten agreement was that they were in the city of whichever border control met them, and thus incarcerated them in the coastal camps, first. How crestfallen were those who, hunting the hopes of Ul Qoma, landed in Besźel.

(p.69)

Or consider another passage from the book’s climactic conclusion, when two buses, one located in each of the two cities, accidentally collide at a finely cross-hatched intersection:

‘They were buses taking refugees to camps. They’re out, and they haven’t been trained; they’re breaching everywhere, wandering between the cities without any idea what they’re doing.’

I could imagine the panic of bystanders and passersby, let alone those innocent motorists of Besźel and Ul Qoma, having swerved desperately out of the path of the careening vehicles [before] trying hard to regain control and pull their vehicles back to where they dwelt. Faced then with scores of afraid, injured intruders, without intent to transgress but without choice, without language to ask for help, stumbling out of the ruined buses, weeping children in their arms and bleeding across borders. Approaching people they saw, not attuned to the nuances of nationality – clothes, colour, hair, posture – oscillating back and forth between countries.

(p.328)

If The City & the City is ostensibly about a murder case, albeit one set in two weirdly segregated cities, what does this sporadic appearance of the refugee introduce? In this second passage especially, the visceral image of a refugee, child in arms, literally ‘bleeding across borders’, is loaded with powerful symbolic resonance. The citizens of Besźel and Ul Qoma see the refugee’s blood when it is in their own city, but they work hard to ‘unsee’ it when it is not. Conversely, the only thing that the refugee ‘unsees’ is the border itself. The refugee’s arrival reveals the extent to which the border’s very existence is predicated on a kaleidoscopic politics of (in)visibility.

Borders are themselves here immaterial; rather, Miéville demonstrates, it is the imaginative participation of us all that keeps them in place. When citizens of these divided cities are faced ‘with scores of afraid, injured intruders’, their habitual fear for the breach of their own internal borders overrides a compassionate response to violence and displacement. Arbitrary markers of difference – ‘clothes, colour, hair, posture’ – eviscerate the possibility of a cross-border politics that recognises that most essential, corporeal marker of humanity: ‘blood’, something we all have in common.

Nevertheless, in throwing the consequences of these spatial politics into such sharp relief, Miéville does offer us some redemption. With The City & the City, a speculative narrative that appears not so much to depart from, but actually to predict the geographic realities of contemporary Europe, he asks us to participate in a different imaginative project. If the figure of the refugee is in Miéville’s novel a threat to the existing order, that threat is framed here as an opportunity for transgressive liberation. For the refugee reveals to the citizens of Besźel and Ul Qoma the dehumanising violence of routine spatial constrictions as they impact not only on those arriving from outside their city-states. The refugee also reveals the crippling psychological labour undertaken by those who are already citizens, and who work so hard to imaginatively restrict their own movements and mobilities. In this simple, if extreme, speculative scenario, Miéville asks us to meditate on what exactly it is we unthinkingly choose to see, and just as importantly what – and who – it is that we habitually choose to unsee.

Recommended Reading:

Davis, D. (2017) ‘Urban Warfare, Resilience and Resistance: Leila Abdelrazak’s Baddawi’

Davies, D. (2017 ‘Hard Infrastructures, Diseased Bodies’

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (2018) ‘Shadows and Echoes in/of displacement. Temporalities, spatialities and materialities of displacement’

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (2017) ‘Disrupting Humanitarian Narratives’

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (2016) ‘Palestinian and Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: Sharing Space, Electricity and the Sky’

Montieth, W. Agendo, D. Karangizi, R. Peters, N. & Ongwech, J. (2018) ‘The Patterned Legacies of Displacement in Uganda: Reflections from the African Mobilities Exhibition’

Qasmiyeh, Y.M. (2018) ‘Necessarily, the camp is the border.’

Qasmiyeh, Y.M. (2018) ‘It is a camp despite the name.’

Featured image: Simon Rowe’s Mapping of Miéville’s The City & the City.

2 comments