A Successful Alternative to Refugee Camps: A Greek Squat Shames the EU and NGOs By Zareena Grewal, Yale University

City Plaza Hotel is no longer a hotel. As a business, it shuttered years ago. But the abandoned seven-story building with faux art deco charms is now home to about 400 people. They’re made up of two groups: Greek anarcho-communist activists, and people who have fled war, poverty, or persecution in Muslim-majority countries.

Bustling with political activity, City Plaza is now a squat organized like a radically egalitarian co-op. When I visited last October, I found the chaotic buzz and aesthetic of a college dorm: cheap furniture, music from competing speakers, walls lined with political posters, and sign-up sheets for an open mic night and shifts in the kitchen or nursery. Large portraits throughout the building featured the faces of the residents passing before me: men and women who chatted in Farsi, Arabic, Urdu, and English. A gleeful herd of children roared up and down the stairs as a smiling Kurdish toddler trailed them, determined to keep up despite the makeshift prosthetic replacing her left foot, which she lost in a bombing.

In the cafeteria, a noisy house meeting was conducted in English, with people seated by language around blue Formica tables. Through designated translators, residents made slow, laborious, collective decisions about mundane problems, like how to manage nosy children who cannot differentiate between the hotel’s common areas and its private bedroom-apartments. Wafts of curry stew crept into the cafeteria each time the adjacent kitchen door swung open. Christian Herrera, a Greek man wearing black Adidas sneakers and a cut-off Korn T-shirt that revealed tattooed arms, looked weary from molding chickpea batter into falafels. But, he told me, “We are a model for the rest of Europe and outside of Europe. Lots of people come here to see how we do things.” Angela Davis, the distinguished African American civil rights activist and Marxist feminist scholar, visited in December.

In Europe, which has had wrenching debates over whether and how to accommodate refugees and migrants—more than 2.5 million applied for asylum in the EU in 2015 and 2016—the City Plaza model is a rare one that does not appear destined to provide a template across the continent. In most cases, refugees and migrants who reach Europe are deported or indefinitely detained in camps, some of which operate more like prisons by severely restricting movement. A minority will be accommodated—where the political will exists to do so—along the lines of the resettlement model in Germany.

But in Greece, which as a first point of entry for many migrants has borne a disproportionate share of the housing challenge amid economic malaise, City Plaza serves as a home while making a political point. Olga Lafazani, a Greek academic and one of the founding members of the collective, says it’s not just about finding a more humane response to the refugee crisis. “Our idea was not to make a thousand City Plazas,” she said with a laugh. The squat, she explained, has an expansive definition of the term “refugee” that includes migrants fleeing any war, political persecution, extreme poverty, and environmental devastation; it’s a rejection of the legal distinction that distinguishes between different kinds of need for migration. City Plaza residents are either waiting for formal resettlement after having had their asylum applications approved or people who have managed to escape the camps. Coming in search of basics like shelter and food, they are also welcomed with private bedrooms, bathrooms, and balconies.

Lafazani characterized City Plaza as an “antagonistic political example” meant to shame both the state and the NGOs. “If we can do it without institutional funding, without any kind of resources from the state or from the NGOs, without any of us being employed here, just with people who offer their time—no specialists—then the fact that the NGOs and the state are not doing [it proves] they choose to have the camps.”

Since June 2015, an estimated $803 million in humanitarian aid has poured into Greece for hosting 60,000 refugees and migrants, making it the “most expensive humanitarian response in history” when broken down to cost per beneficiary. Greece was a corridor for those en route to wealthier European countries until March 2016, when a deal reached between the EU and Turkey, as well as the closing of Greece’s northern border, trapped 60,000 refugees and migrants in the country. The EU-Turkey deal was intended as a way to address the flow of arrivals into the EU. Turkey agreed to take back those who had traveled from Turkey to Greece but were not granted asylum; in exchange, the EU would step up its resettlement of Syrians coming from Turkey, ease visa restrictions for Turkish citizens in the EU, and pay billions in aid to Turkey and Greece. In practice, resettlement has not kept pace and conditions in the refugee camps have deteriorated. Ten days after the deal was made, Greece’s right-wing Minister of National Defense, Panos Kammenos, received an annually recurring $74 million for his defense budget, from the funds the Greek government received from the EU. Detention camps, guarded by soldiers and police and known as “hotspots,” were up and running within two weeks.

Back in City Plaza, refugees such as Sultan are front and center in the mind of Nasim Lomani, a founding member of the collective and one of the activists “in solidarity with the refugees” (they eschew the NGO language of “volunteers”). A 36-year-old Afghan with a tough punk exterior and a soft voice, he himself is a refugee from an earlier generation. “The issue [is not just] the 400 people here,” he told me. “We care much more about the other 60,000 people that are outside. Because they [government officials] hide them. No one sees them.”

Between drags on his cigarette, he explained, “We try to scandalize the practices of the state, the EU, and even the NGOs—the way that they work with refugees, and create a pathetic population of dependency on the state.” City Plaza, he added, is not about “taking care” of the 400 people living there. “They do it by themselves. They are very strong people. They manage to arrive here. They escaped wars. They can organize a house like this themselves.” Indeed, the squat’s modest, in-house medical clinic is staffed by refugees who were medical professionals in their home countries but are not licensed to practice in Greece.

In the U.S., leftist anti-homelessness activists sometimes occupy abandoned buildings and operate squats in progressive pockets of the coasts. The City Plaza activists are much more ambitious. The old hotel is located in one of the most politically conservative neighborhoods, Aghios Panteleimonas, a former stronghold of the fascist Golden Dawn party. Weeks after the EU-Turkey deal was signed, the leftists broke the locks of City Plaza, seized the building, and reconnected the utilities while neighbors threatened to call either the police or the local fascist gangs to force them out. The squatters held their ground and established City Plaza as a home for people fleeing from Afghanistan, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Eritrea, Somalia, and Nigeria. Over the past 20 months, City Plaza has served as home for 1,008 of them; they have staved off the owner’s eviction attempts and won over some of their neighbors by improving the blighted hotel and cleaning up the street.

Thus politically vulnerable people, fleeing war or extreme poverty, find themselves in a position of standing up to everyone from concerned neighbors to actual fascists to the state. And perhaps it’s fitting, since being displaced from home and treated like a criminal would certainly unsettle one’s faith in institutions. Lafazani explained that the refugees are told upfront that City Plaza is a squat, not an institutional space, but that some of the refugees come to see the value of their radically egalitarian project slowly, through actions rather than words. She described an early morning when the water company arrived to shut off their water and they woke all of the residents and made a human chain on the sidewalk to prevent company personnel from entering. A small, if temporary, victory: The water stayed on. “Then the refugees really understood that it’s not a [shelter] from the state.”The trappings inside City Plaza clearly reflect the founders’ leftist politics. There’s a seating area used for screening movies such as the Iranian Marxist feminist film Women Without Men. Along the wall, novels in English, Arabic, and Farsi are populated with clear-eyed Muslim characters who defy social, sexual, and political norms: Alaa Al Aswany’s The Yacoubian Building, Naguib Mahfouz’s Palace Walk, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. But the founders insist their aim is to find common cause, not to indoctrinate those living at the house, most of whom, Lafazani acknowledges, “don’t come because they are leftist.” Some of the house’s residents are Arab Spring activists who arrive with their own discourse of justice, rights, and dissent already well formulated; often, it is religiously infused, and it shapes life at City Plaza.

When the squat hosts dance parties, they are dry events, because some observant Muslim refugees do not drink alcohol; the hotel’s bar area has been transformed into a café that serves thick, steamy Turkish coffee and cardamom-flavored tea. If the values of some strains of Islam seem an odd fit with Marxism, the organizers insist that religious and ethnic differences have not been a source of conflict for the residents; nor, as one might expect, does one find residents debating differences in political ideology or gender norms. There is plenty of mundane conflict, but most of the daily bickering is chore-wars. “Damn Europe!” curses a young Syrian man in a short documentary about City Plaza. “I came for freedom and stability but I’m washing dishes.” Taped to a pillar in the hallway is a handwritten copy of the celebrated Greek poet Konstatinos Kavafis’s poem “Ithaca,” decorated with the stray crayon marks of a refugee child. The poem draws out the metaphor of life as a journey to Homer’s ever-elusive destination—Ithaca—but the verses take on another layer of poignancy in a house full of refugees who never expected to get trapped in a country with a 20 percent unemployment rate. Kavafis, a social rebel who lived and wrote from Alexandria and Istanbul, represents a shared Greek-Muslim Ottoman past. His words gesture toward the possibility of the Greeks and refugees forging a new, provisional, cosmopolitan future:

And if you find her poor, Ithaca has not defrauded you.

With the great wisdom you have gained, with so much experience,

you must surely have understood by then what Ithacas mean.

*

Suggested readings on this topic:

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (2018) “Contextualising the Localisation of Aid Agenda”

Ramakrishnan, K. and Stavinoha, L. (2017) “Volunteers and Solidarity in Europe’s Refugee Response”

Ozturk, U. (2017) “Broken Borders: Overcoming Personal and Cultural Barriers along the Refugee Route”

Trotta, S. (2017) “Faith-Based Humanitarian Corridors to Italy: A Safe and Legal Route to Refuge”

Western, T. et al. (2017) “ΤΣΣΣΣ ΤΣΣΣ ΤΣΣ ΣΣΣ: Summer in Athens – A Sound Essay”

Zaman, T. (2017) “Athens and the Struggle for a Mobile Commons”

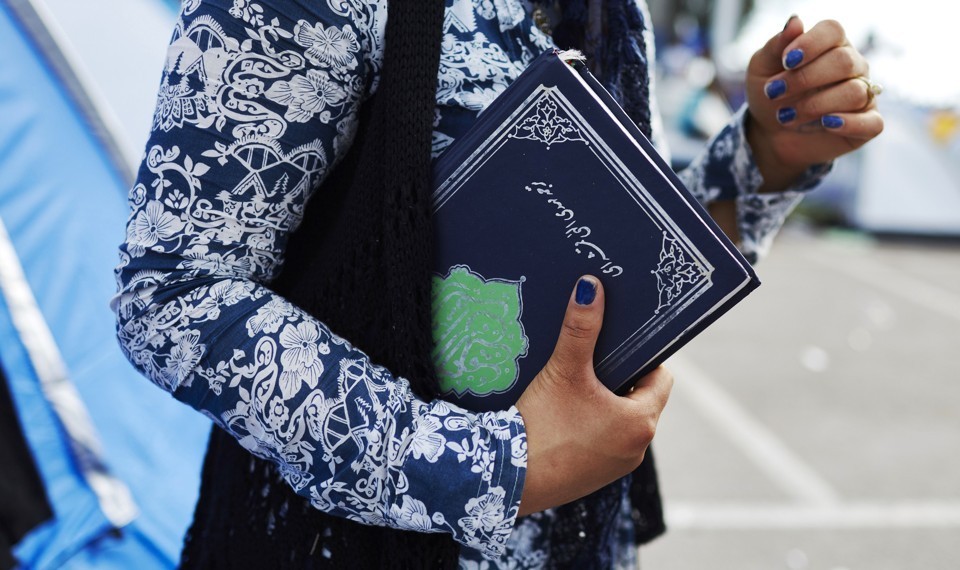

Featured Image: A Muslim Refugee in Greece (c) Getty/Pierre Crom (re-posted from original article in The Atlantic)

***

This piece has been reposted from The Atlantic. You can read the original here.

13 comments